Painting by Numbers

‘Bauer may have had the capacity to remember colours in the way that a musician remembers notes.’ David Mabberley

We are thrilled to launch ‘Painting by Numbers’ a digital experiment, designed and built by the State Library’s DX Lab, with the content researched and curated by Professor David J Mabberley AM. It brings together, for the first time online, nearly 300 original works by botanical artist Ferdinand Bauer from cultural institutions across Europe, the United Kingdom and Australia. Our international cultural organisation partners include: Natural History Museum London, Naturhistorisches Museum, Wien, Bodleian Libraries University of Oxford, The Linnean Society of London and Royal Botanic Gardens Kew.

‘Painting by Numbers’ has been made possible through a gift from the Belalberi Foundation

Ferdinand Lucas Bauer (20 January 1760 – 17 March 1826), an Austrian botanical illustrator, is widely held to be the greatest natural history painter of all time – and certainly the greatest to have worked in Australia. His work of biological illustrations, which meld scientific accuracy with artistic verve, have received the highest praise – from his contemporary Johann Wolfgang von Goethe and continuing to today’s critics.

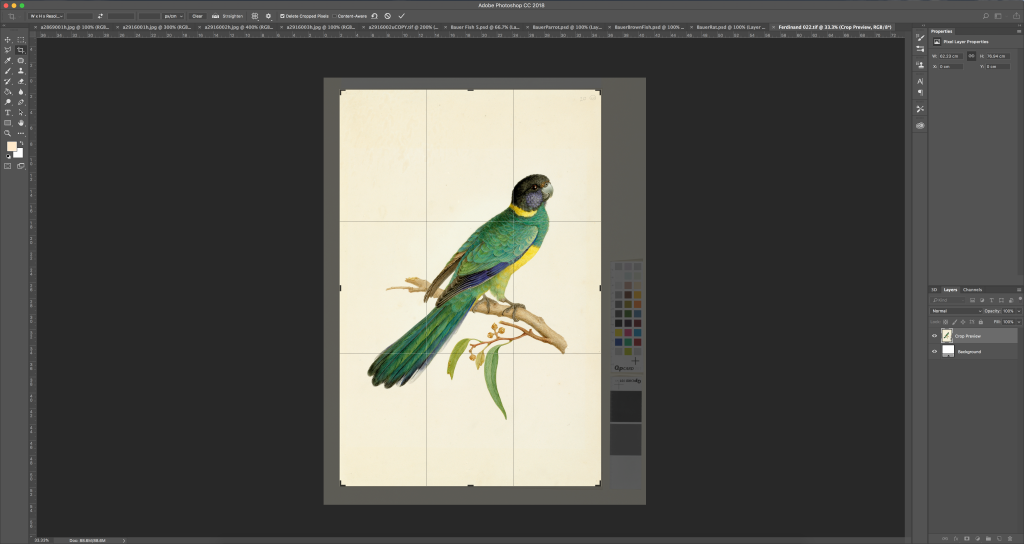

Among his best work are the illustrations of animals and plants Bauer observed in Australia between 1801 and 1805, during Matthew Flinders’ circumnavigation of the continent and Bauer’s later residence in New South Wales and on Norfolk Island.

Unlike his equally talented brother Franz, Ferdinand was a fieldworker. He recorded animals and plants as he found them in the wild, not relying on captured or dead specimens drawn in the comfort of the studio. His drawings have a vivacity and grace while, at the same time, maintaining scrupulous scientific accuracy.

Bauer’s watercolours were not only faithful records of fauna and flora — a few of them have since been designated ‘types’ for names of thitherto undescribed species, including Australian fish and plants. Some of his field sketches on Norfolk Island depict animal and plant species now extinct and, through the ‘cracking’ of his colour-code by David Mabberley and colleagues since 1999, it has been possible to recreate the coloured illustrations of those lost species. For the first time online, you can explore the genesis of his colour-coding technique.

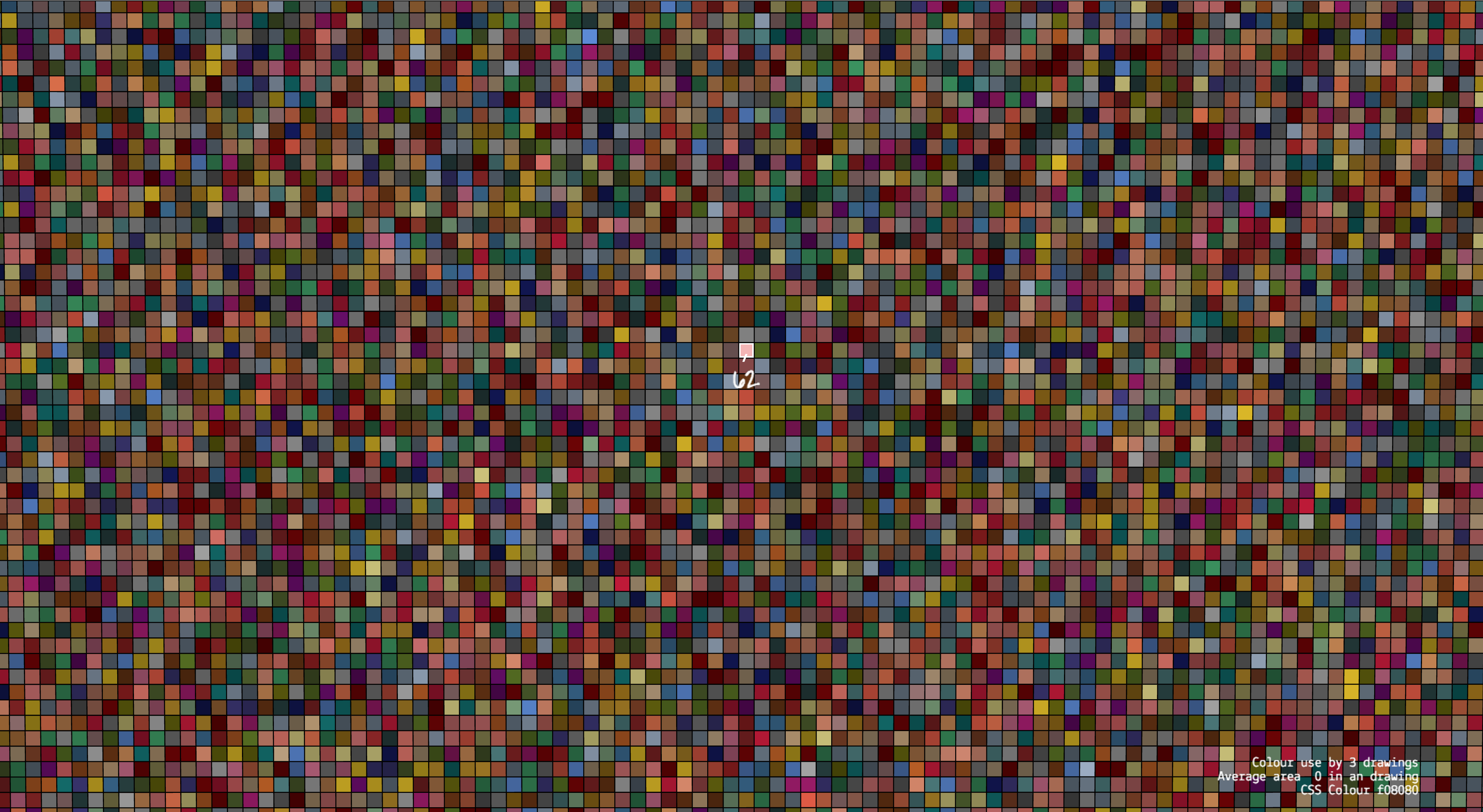

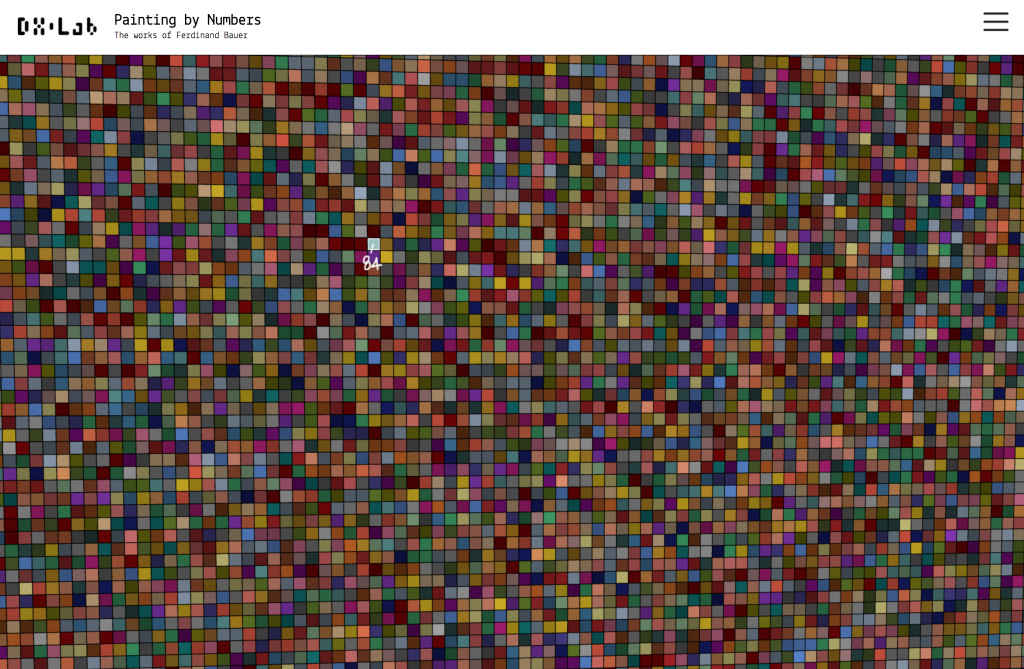

This website is one of the larger experiments that the DX Lab has designed and built. One of the challenges has been to apply contemporary design with content that is very traditional. How do we utilise the latest technology whilst allowing the beautiful images to speak for themselves? One of the special things about Ferdinand Bauer’s work is the incredible detail and his remarkable ability to recall up to 1000 colours in his mind. This was something we really wanted to get across as soon as you enter the website.

This website is also accompanied by a book that goes deeper into the stories about Bauer and his work, so we didn’t want to just replicate the book – they needed to compliment each other. The strength of this website lies in the amount of data that is accessible on the web and we have used many open source sites to do this including the Atlas of Living Australia.

The team that has designed and built Painting by Numbers includes:

Paula Bray, DX Lab Leader, Carlos Arroyo, Web Developer, Georgina Carberry, UX and Design, Megan Reilly, Digital Producer, Leonie Jones, Media Producer and Professor David J Mabberley AM, Guest Curator.

The aim has been to allow viewers to experience a digital version of Bauer’s colour palette and to immerse themselves in the homepage data visualisation, before diving into the details of the content. This is a playful entry into the website and allows the user to start to understand the depth of which Bauer could recall colour. The intention has been to keep the user on the homepage for a time playing with colour before entering the site. When you click on one of the colours a pixelated version of one of the images that use that colour will appear and then slowly disappear.

Making the videos and Sliders: By Leonie Jones, Media Producer

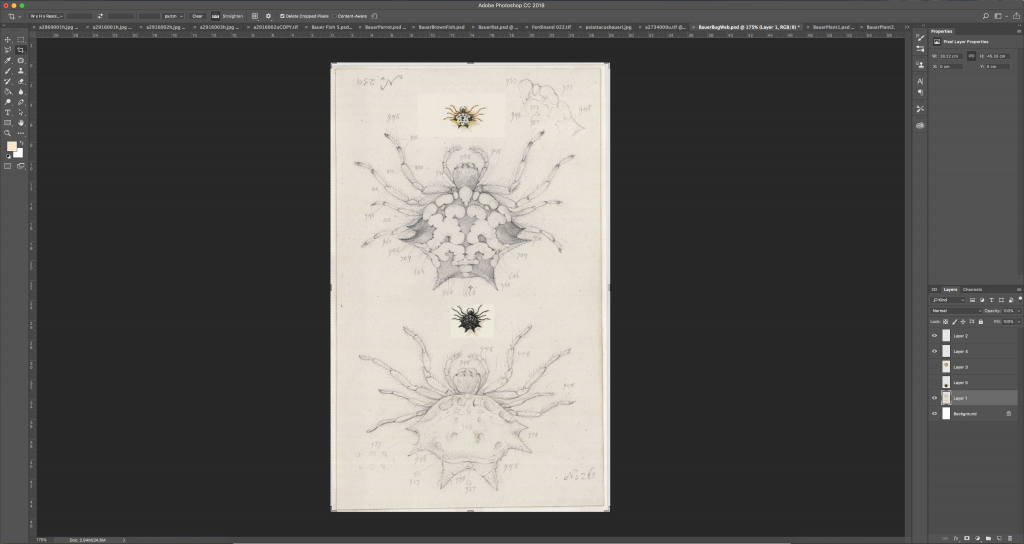

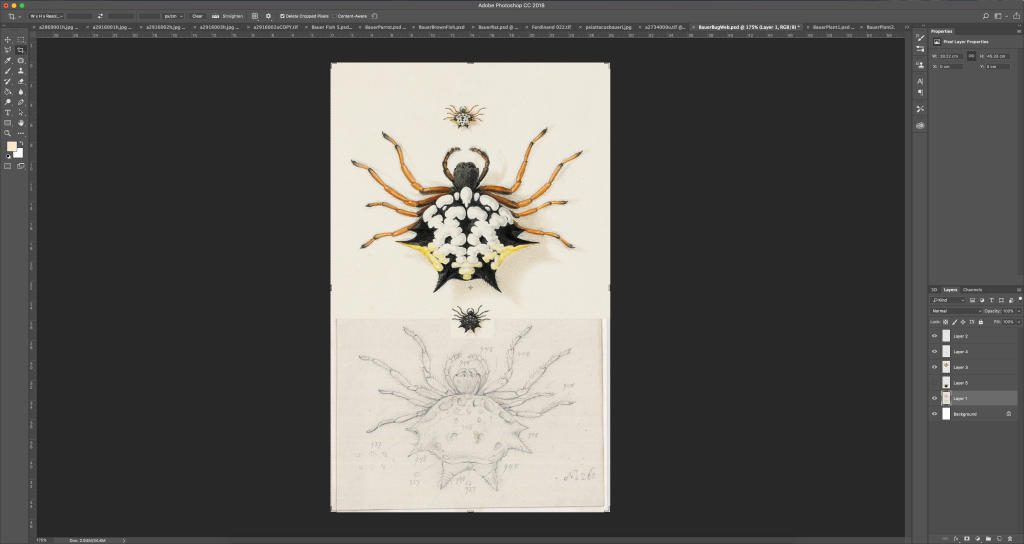

On first view, the pencil sketches where Bauer uses the ‘Painting-by-numbers’ technique of recording colour and texture details with hundreds of memorised numbers, clearly demonstrate his extraordinary memory and skills of observation. However, it is not until we see the resulting watercolour or print, that we are truly struck with the transformation of life-like detail and beauty in the final works.

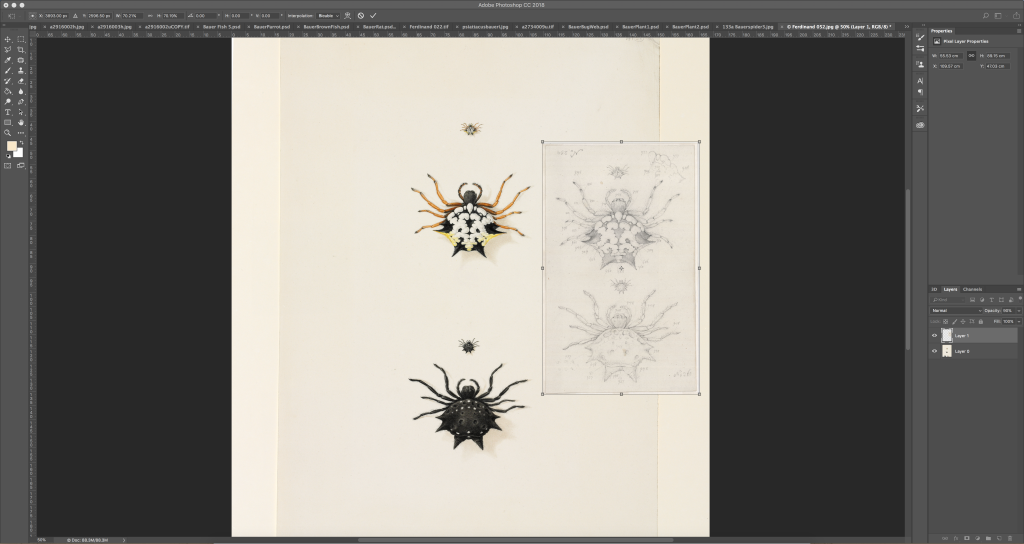

With this in mind, and given the unprecedented access to many of the matching pencil and watercolour works that this exhibition has offered, we knew it was necessary to create a platform where we could showcase both ends of Bauer’s creative process. Rather than simply sitting each matching work side by side, the best way to bring his process to life and allow exploration of it, was to use ‘slider’ technology which reveals a ‘Before and After’ view of the works.

By allowing the details of Bauer’s observations to unfold before our eyes, slider technology not only afforded us a greater appreciation of his technical prowess as a great artist but has allowed us to immerse ourselves in this thoughts and offers us a rare insight into the man himself.

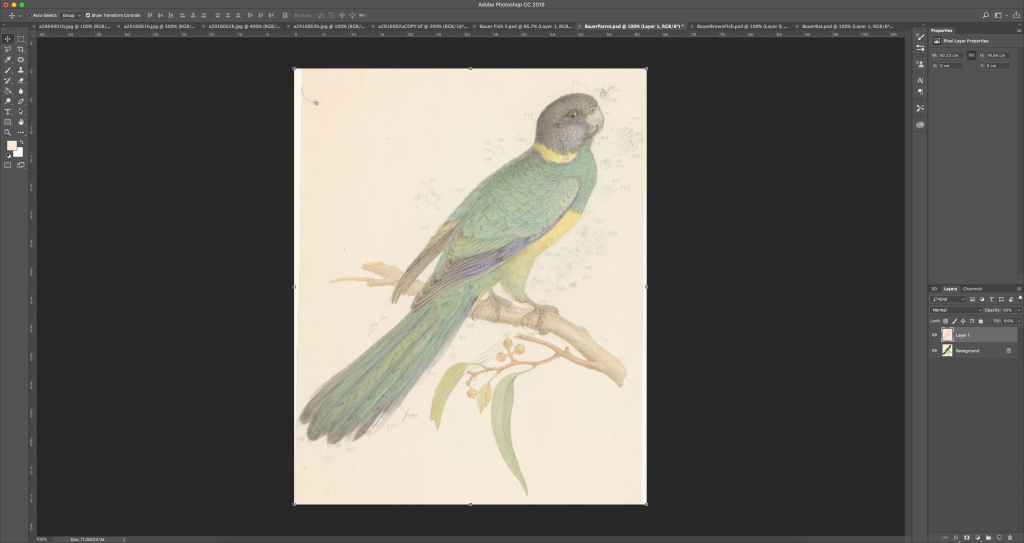

The first step I took in producing the sliders was to search the collection of Bauer’s works we had access to and select matching high-resolution images of the pencil sketches and watercolours. Many of the watercolours were prepared from one pencil sketch, however some are an amalgamation of two pencil drawings. Some are complete drawings that match the watercolour almost exactly and some are just fragments of details that Bauer later worked up into a complete watercolour of the subject.

To begin, I opened each matching set of high resolution digitised images in Adobe Creative Cloud Photoshop and I cropped each image to remove any extraneous background details, such as backing cards used to give the dimensions of the original works, to leave only the original work itself.

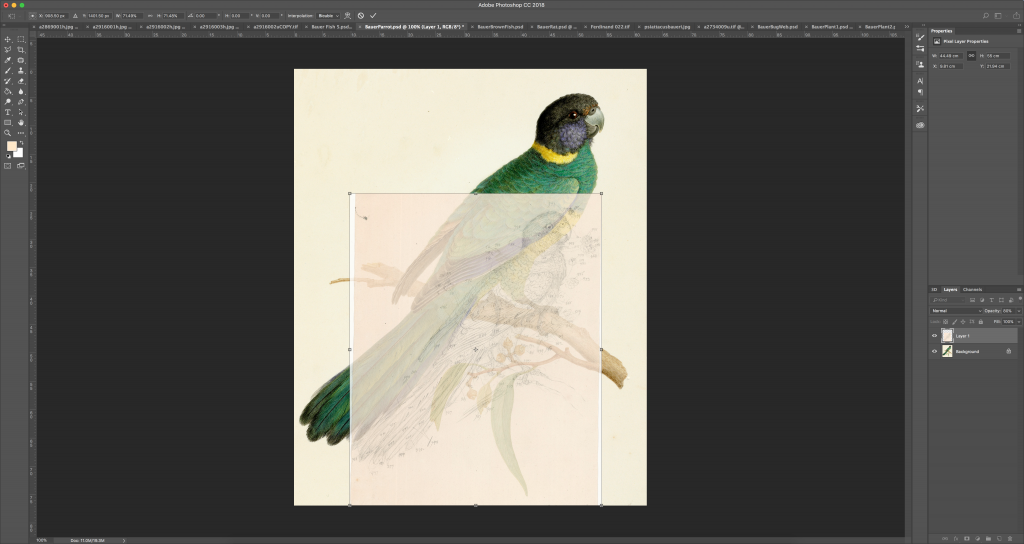

Given that none of the digitised images were exactly the same dimensions or resolution, I then created copies of each image to similar dimensions, leaving the resolution as high as the original so that I had room to manipulate the image without losing detail. Some of the works had the subject matter placed very differently on the page between the pencil sketch and the watercolour, so at this stage, I left those at the same dimensions. In the case of original pencil works which were much smaller in size and contained only a small detail of the final watercolour, I created a colour-matched background layer for these in the next step, so that they were the same dimensions as the matching watercolour image.

None of the original matching images were exactly aligned, so the process of lining up each image to allow the slider to reveal the exact same detail on both was quite painstaking. In order to do this, I created a multi-layered Photoshop files (PSD) for each of the matching images. I aligned and manipulated each image by reducing the opacity of the overlapping image/layer to 50% – 80%, so that I could see the layer below. For some I adjusted the scale of the images to match, however some images required more complex manipulation to adjust the perspective and orientation in order to allow for any distortion in the original.

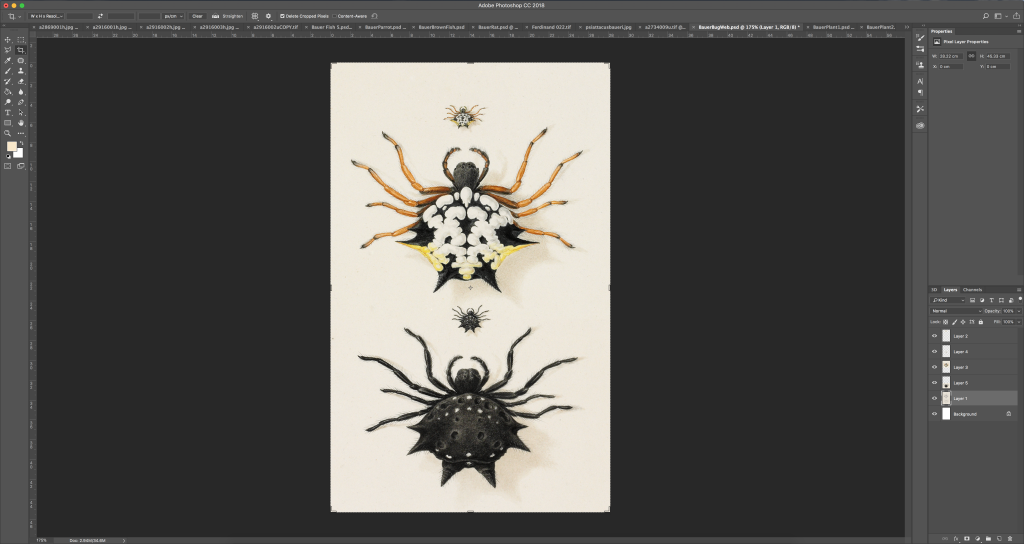

In manipulating these images to match, I was very much aware of the balance between the integrity of the original image and adjusting the images just enough to illustrate the transformation between the works. This was not always an easy balance as Bauer often sketched the main subject of the drawing in the middle of the page and then placed individual details of the subject on either side or at the bottom of the page. In most instances, I chose to match the main central image and leave the details where they were to show his original placement and intent. However, in some images, I have moved certain overlapping or unaligned details for clarity of the reveal between images. See the example of the Christmas Spider images below, where I moved the placement of the individual spiders on the page in order for better alignment, but not changed any of the details, including the carefully drawn shadows, in either image.

Finally, I exported each individual image/layer out of Photoshop separately at screen resolution of 72ppi and to exactly the same dimensions, so that the matching images would align perfectly. With my work done, I then handed over to Carlos Arroyo who created the code for the sliders in our website.

Stay tuned for our next blog post where we will be doing an in-depth story on the technical development of the website with the developer Carlos Arroyo.

Comments

I studied Bauer’s work in the Natural History Museum in Vienna. Your execution of his art is a marvel. It will help many others who study science illustration and practice watercolor painting.

A truly fascinating project. I love it. And very cleverly done in terms of matching the original sketches with the finished artwork.

I’d really like to see a colour chart which aligns with all his numbers for the Australian collection. Is one available? Can you make it available online? (I appreciate that the screen colours will vary a bit from the originals …but not so much as to make it unusable)..more below.

I’m curious about his Gymea lily where the colour seems so wrong (far too pale in most reproductions). Was his original colour coding right and the colours have faded? Or was his original colour coding wrong?

Is there any first hand evidence that Bauer did not use colour charts but simply “remembered” the 1000 plus colours? That seems extraordinary but may be true. ….Any written records which described his mode of working, for example? If the only “evidence” is negative evidence….ie that we can’t find his colour charts then that is hardly proof that he worked by memory. It’s clearly a lot simpler to just use a colour chart alongside the specimen. The colour of the specimen varies with the light, of course, and is not a constant. (Bright sun vs overcast conditions or setting sum…all have different qualities in the ambient light. So he clearly had to make a call ….but within a single bloom or inflorescence much of the colour (with watercolour anyway) could be achieved via dilutions of the dominant pigment or via slight additions to the original pigment. Again, much easier to do with a colour chart than from memory. And, if he was working with a red flower for example, most of the colours would be variations of red…so he would not need to be manipulating a chart with 1000 colours on it…just a sub set…most of the time). Clearly he was remarkable: both as draftsman, painter and scientist. Hard not to be amazed and your exhibition adds to the amazement.

Thanks very much for your comments Lloyd! We ‘constructed’ the ‘Australian’ chart by comparing the numbers on drawings of WA plants (refs in the book) with living ones. No chart has ever been found for either of Bauer’s two expeditions and no-one ever mentioned him using one, though on the Norfolk Is. drawings are links to the Estner 1794 mineralogical chart (fully discussed in the book). That is all we have. The speed with which he worked supports the idea that he was not juggling a cumbersome chartt of 1000 shades – but, as discussed in the book, there is room for other interpretation.

The Gymea lily is wrong in all sorts of respects as is again discussed in the book.

Best wishes

David Mabberley

fascinating. Hope more people get to view these sliders More interesting than the actual exhibition

This is fabulous, surprised me. I thought the images would be enough for me, but seeing how he did it is amazing.

Fantastic, thank you. I thought I knew a little about natural history art but this takes my understanding to a whole new level. A pity I am on the Gold Coast and will not be able to visit the Library.

It is wonderful how the internet and computers are discovering and bringing these treasures to a wider audience.I am so thrilled with this revelation.I completed a diploma of fine Art; and have studied Fine Art for the past fifty seven years;it is delight to see this.Congratulations on your work,Best regards Colin Eden.

Some wonderful history. Well done.