Field of View

This post describes the results of Mike Daly’s research at the DX Lab, which has been made possible through the DX Lab’s Digital Drop-In Program. The program supports quick sprints of exploration using innovative technologies to engage with the Library’s collection and data sets. Mike’s research is supported through a gift to the State Library of NSW Foundation – a not-for-profit organisation which supports key Library fellowships, innovative exhibitions and landmark acquisitions.

Past & Present

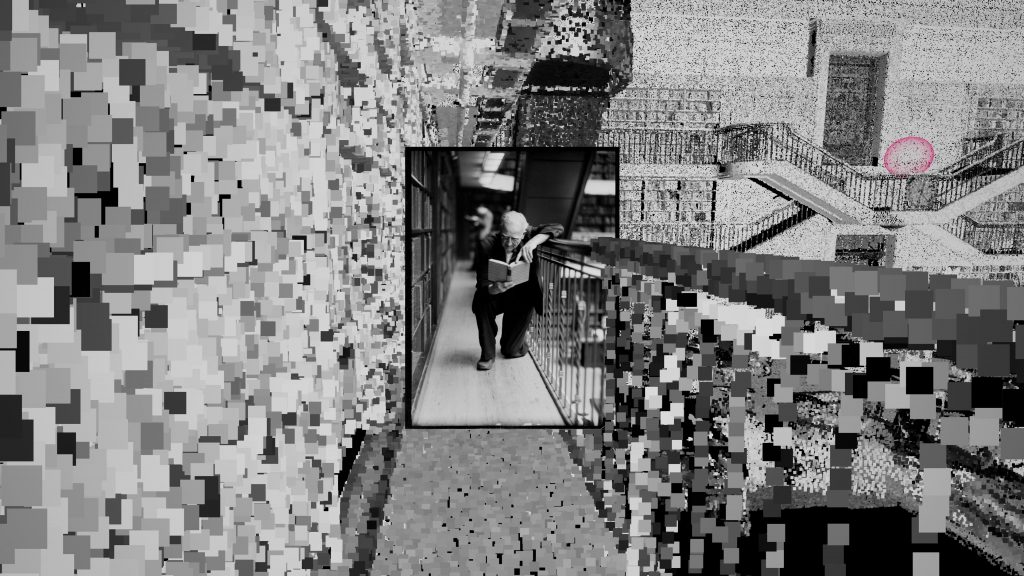

You know when someone takes a picture of a historic photograph in the exact place it was originally taken? There’s something fascinating about seeing the old world line-up perfectly with the new – how it bridges our day-to-day lives with those of the past.

My research proposes an interactive experience that sets historic photography within a LiDAR scan of the environment where the photographs were originally taken. Central to this, is the idea that the user can then view the different photographs from the photographers’ perspective.

There are many similarities between LiDAR scanning and early photography: long exposure times, the size and weight of the equipment, the expense, the intersecting of cutting-edge science and art, the difficulty in working with the results, and the dream-like imagery they can create.

In some ways LiDAR scanning isn’t separate to photography, but a younger sibling of it. It’s photography with depth. For me, realising this added another level to the proposal – perhaps it could explore not just the content of the photography but the development of the medium itself.

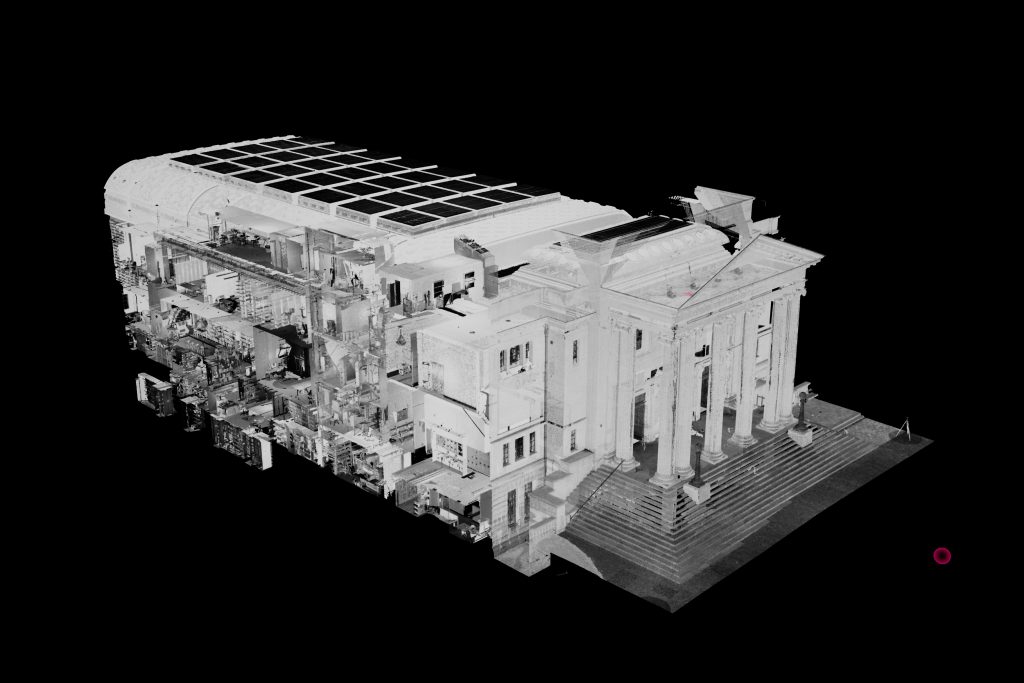

My original plan was to create LiDAR scans of Martin Place in Sydney and fuse it with the Library’s rich collection of historic images from the area, so I began the project by doing some test scans. However, it turned out that the Library’s Mitchell Building was LiDAR scanned in late-2016, shortly before construction of its new galleries began. This discovery led me to change tack and give the Library’s point cloud a new lease on life.

The Point Cloud

The entire point cloud is about 12GB in size and contains over half a billion points. My favourite parts of LiDAR scans are the artefacts. Since the scanner takes time to capture the environment, people walking through the Library become warped and stretched, while birds in flight become stray points.

The brightness of the points in the Library’s scan represent the intensity of the reflected laser beam as it returns to the scanner, this may cause something that might look bright to our eyes to appear black to the scanner, or vice versa.

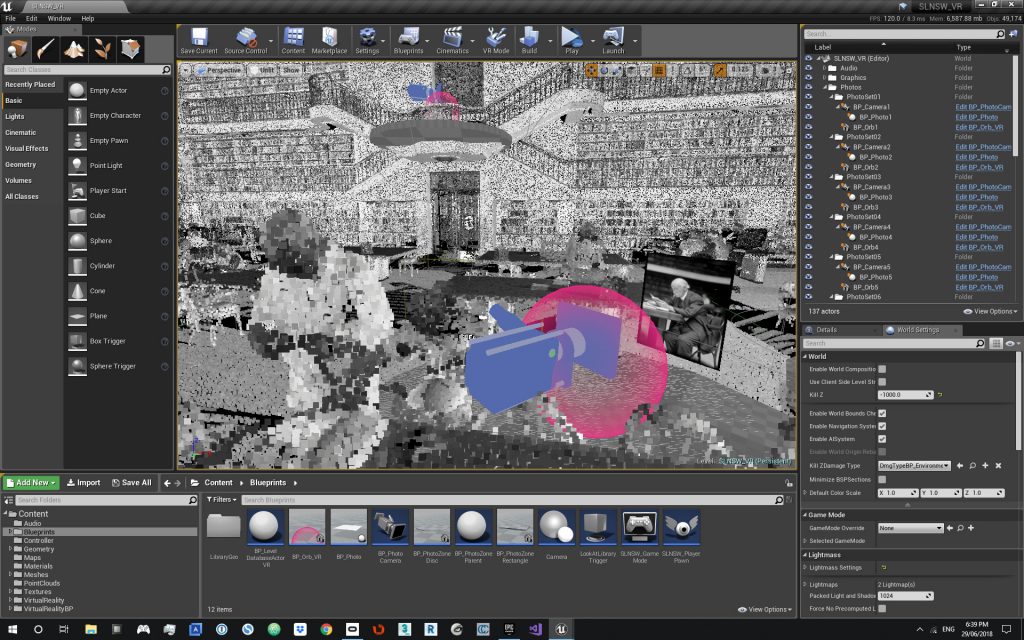

I was interested in presenting the research as an installation, so I used Unreal Engine 4 (a 3D game engine) to create it. Point clouds generally aren’t used in computer games (yet?), so they’re not supported in Unreal, however, a software engineer in Manchester recently developed a plugin for Unreal that allows point clouds to be rendered in real-time.

I custom built a fast new PC to create and run the experience, but even it couldn’t properly handle the entire point cloud of over 500 million points. I could get it into Unreal and run it, but not at an acceptable frame rate.

After trying lots of different methods to reduce the density, I took the entire point cloud and sliced through the rooms surrounding the reading room, foyer and entrance. This reduced the scan to about 90 million points, which the computer was much happier with. What I really liked about this was that it opened up the adjacent rooms like a dollhouse.

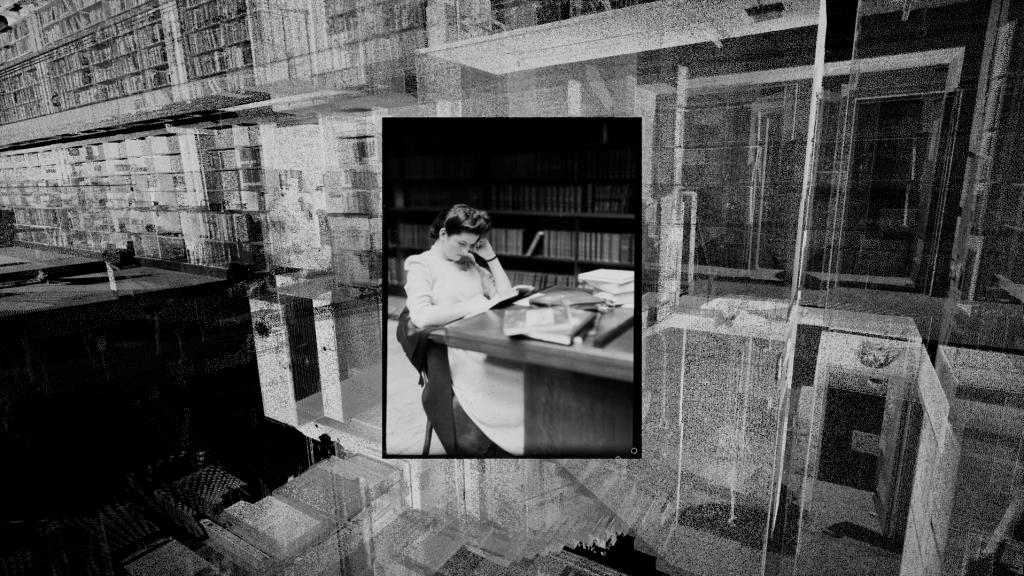

Photographs

It was important to me that the photographs appearing in the experience have people in them so they could engage users on an emotional level. Library’s curators helped me find some beautiful black & white images of people in the Library in the 1940s and 50s.

For every image in the experience, I needed create a virtual camera with the exact same position and angle as the camera that took the original photograph. Using the camera matching feature in 3ds Max, I was able to place reference points on a photograph and in the point cloud at corresponding places. The software then used these points to calculate the exact position, angle and field of view of the camera as it took the image all those years ago.

Building the Experience

With the photography and point cloud now together, I decided to build two variations of the experience – a traditional screen version and a VR version. This allowed me to explore how the different technologies might force the UX design to diverge.

Screen Version

For a long time, I felt that the experience shouldn’t be like a computer game. I wanted something more tangible and tactile, so I developed UX concepts that involved touching real photographs, which in turn triggered the virtual camera to move to the matching image in the point cloud.

After early user testing of the experience I realised that what people really loved was having the autonomy to fly through the point cloud and discover the photographs themselves. There’s a childlike sense of play that older, simple controllers evoke. I can’t wait to build a custom console with genuine arcade controls when the experience is exhibited in the future.

I still wanted to place the user in the exact position that the original photographers’ cameras were placed, so I created floating spheres in the position of each virtual camera. When a user navigates closely enough, they’re suddenly drawn into the sphere and moved to the position of the camera as the photograph fades in.

Virtual Reality

The VR experience had to be handled differently. Allowing a user wearing a VR head-mounted display to simply fly around space can quickly induce motion-sickness. (We tested it. Wasn’t fun.) To avoid this, the user presses a button on the VR controller that casts out a line in front of them and releasing the button teleports them instantly to the end of the line.

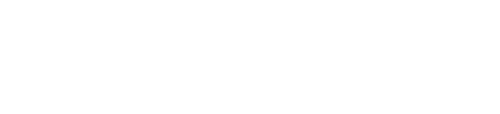

There are two main methods of rendering point clouds: as single pixels (a dot on the screen) or as sprites (a small flat shape). For the screen experience version I chose to render each point as a pixel because things appear transparent when you get closer to them. This allows you to see through walls and people, giving a beautiful ghostly quality to the world.

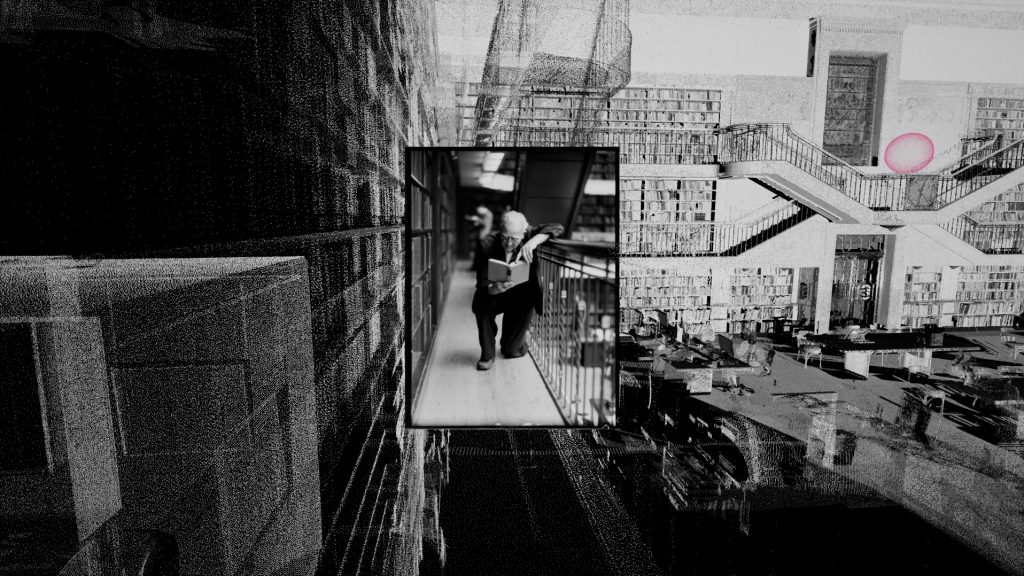

The VR version of the experience, however, worked much better with the point cloud rendered as sprites. Sprites appear larger as you get closer to them, like objects in the real world, which means that things close to you are more tangible. Sprites are slower to render, but because they’re larger you can use less of them. The VR experience uses 15 million points, as opposed to the 90 million used in the screen version.

During testing it quickly became apparent how much the experience of using VR technology could upstage the content. Many users were putting VR goggles on for the first time, so it’s not surprising that they were more interested in exploring the new dimension they’d just discovered than looking at photographs. (It was great seeing Library staff so excited to be up in the balconies around the reading room, where only select librarians are allowed.)

To overcome this I introduced a subtle element of gamification by simply making a pink sphere become white after it’s been visited. Once the excitement of just being in a point cloud begins to wane, discovering all the photographs is a simple challenge that people are drawn to. This adds depth by moving from pure spectacle to an experience that evokes both time and place.

The Future

People’s reactions to the experience have been really positive. At the very least it has opened some people’s minds to the possibilities of gaming technologies, VR and point cloud data in cultural spheres, such as libraries, museums and galleries.

A screen version of this will be available when our new galleries are launched in October.

Looking further ahead, working on this project has given me so many ideas for experiences that could engage the public emotionally and intellectually. We’re at an exciting time in the field of digital interactive work. There’s some really amazing stuff being made, and so much more to come.

Technical Appendix

Software used…

– Unreal Engine – Build the experience

– Point Cloud Plugin – Plugin to work with point clouds in Unreal

– Controlysis – Plugin to map the input of a joystick in Unreal

– AutoDesk ReCap – Combine and edit the point clouds

– CloudCompare – Edit point clouds and convert file formats

– 3ds Max – Camera matching the photographs

– Cinema 4D – Create the 3D credits

– Adobe Photoshop – Prepare the photographs as textures

Hardware used…

– Graphics Card: GeForce GTX 1080 Ti

– Processor: Intel Core i7 8700K 6-Core 3.7GHz

– Motherboard: Z370 LGA-1151-2 ATX

– RAM: 64GB DDR4

– SSD: 1TB NVMe M.2

– VR system: Oculus Rift

Special Thanks

I’d like to thank Paula Bray, Kaho Cheung, Luke Dearnley, Kate Curr, Geoffrey Barker, Robin Phua and Dr John Vallance, as well as the DX Lab, the State Library of NSW and everyone who tested the experience.