We Are What We Steal

Our recent Digital Drop-In, Brett Tweedie, took an interest in researching New South Wales through its crimes and has represented the results in a contemporary, data visualisation that focuses on the topics of people, places and things. We are excited to show you the results of his research in this innovative data visualisation We Are What We Steal.

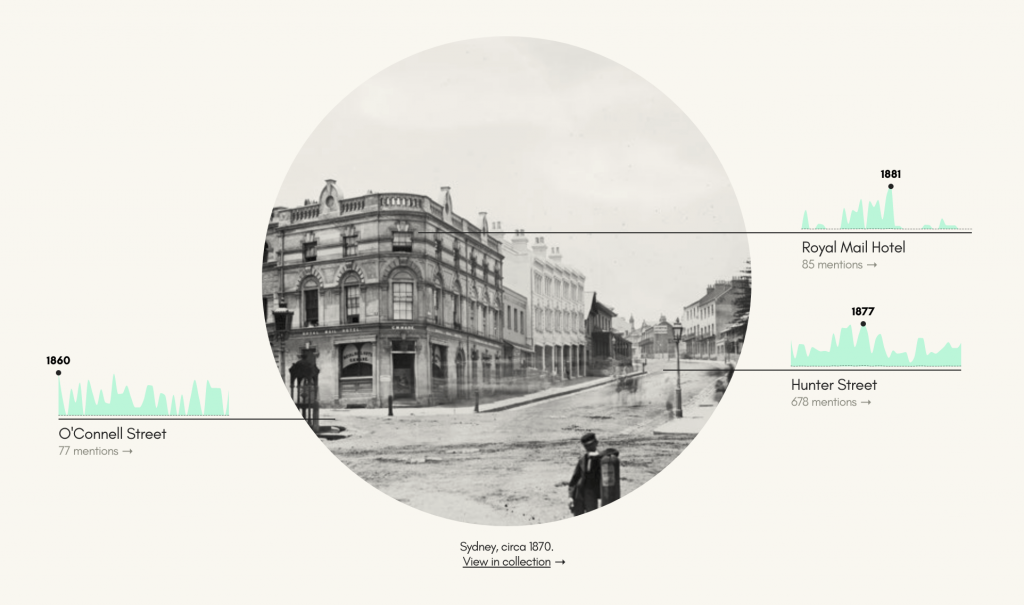

NSW and Sydney in particular, has a rich history of criminality. But crimes do not occur in a vacuum, they are a reflection of the time and place in which they occur. Data visualisation designer and DX Lab Digital Drop-In, Brett, has been researching the crimes recorded in the New South Wales Police Gazette & Weekly Record of Crime and the detailed descriptions that accompany them. His research question has been about viewing some of the ways in which NSW changed over the period in which the gazette was published.

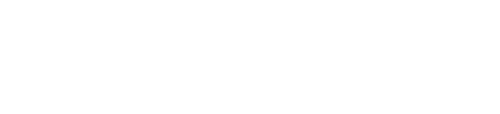

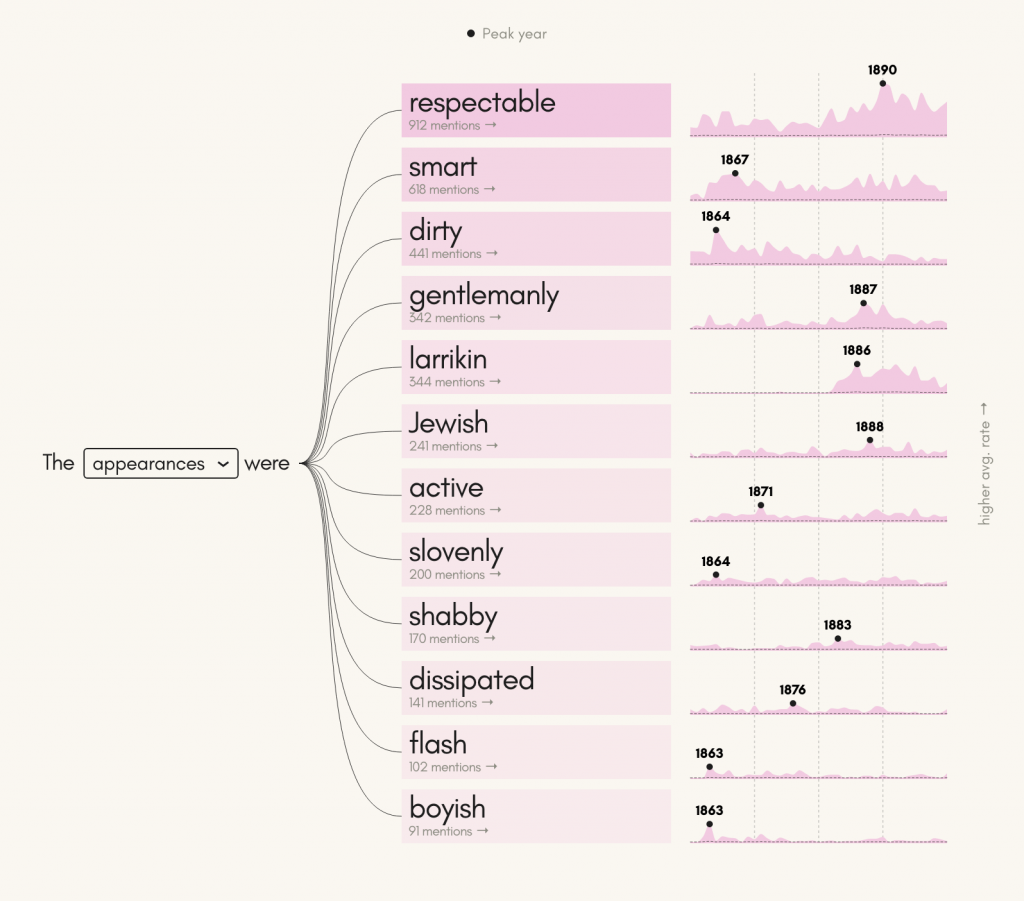

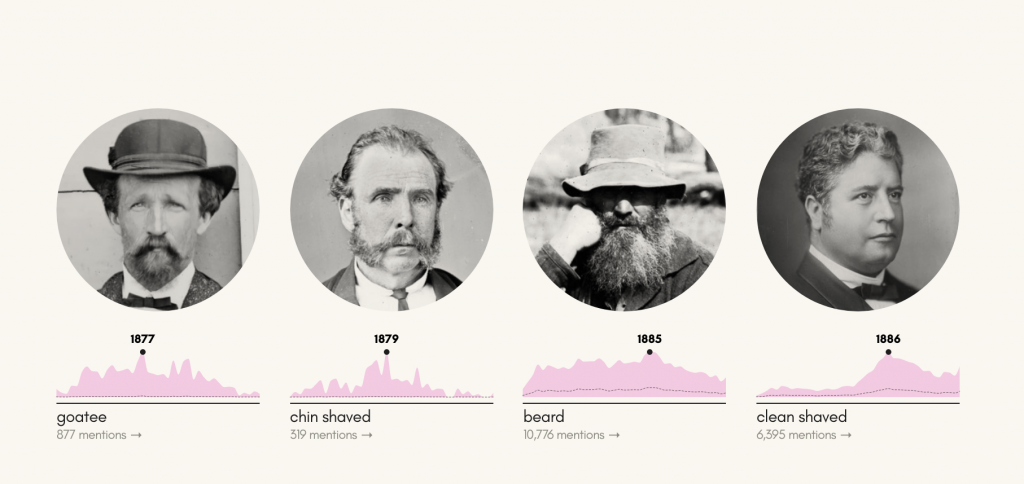

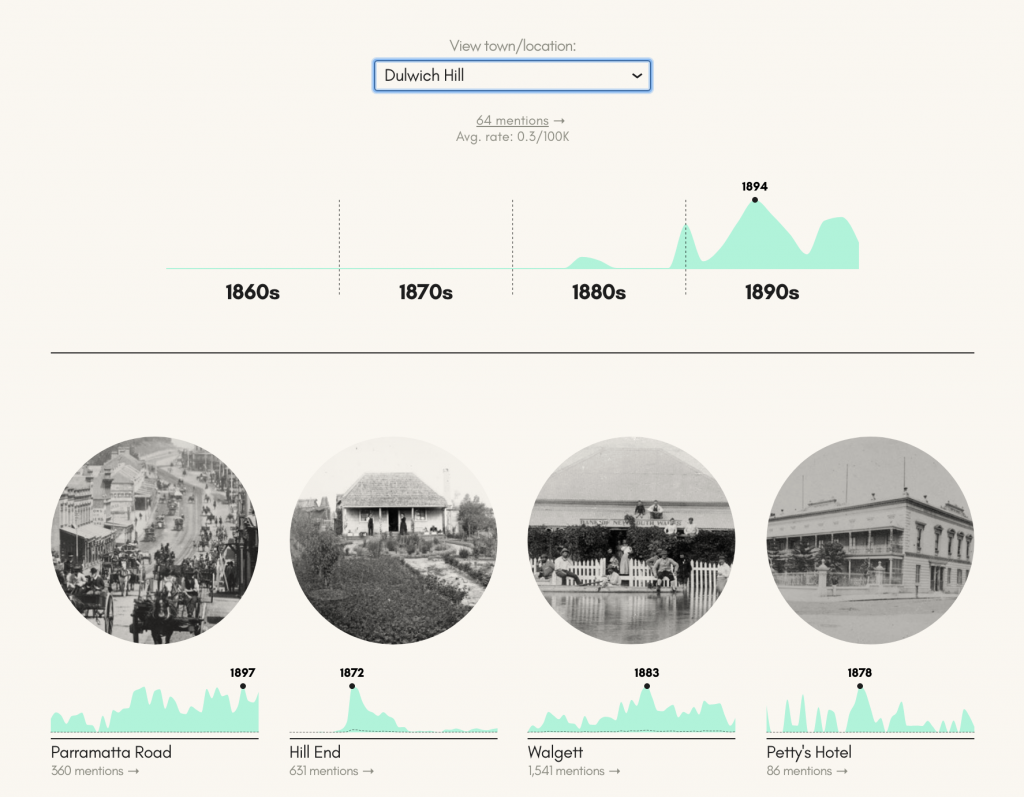

‘This data visualisation looks at the almost 20 million words that were recorded in 41 years of the New South Wales Police Gazette and Weekly Record of Crime from the beginning of 1860 up until the end of 1900 to see what it shows about how the people, places, and things changed in NSW over that period. What was valued? How did people dress? Where did people live? What items did they own?’ — Brett Tweedie

Brett’s research aimed to reveal aspects about a range of subjects, including: fashion, technology, health, wealth, population growth, language, and racism by looking at the descriptions of what was stolen, by whom, where, and when.

Burglaries, stealing from Premises &c. Redmyre.—Stolen, about 8 a.m. the 30th ultimo, from the residence of Mr. Laidley Mort, Redmyre Road, Redmyre,—A,silver Waltham watch, maker’s name and number unknown, steel Albert attached by split rings, and a silver breast pin. By a man about 40 years of age, dark whiskers; dressed in light blue shirt or jumper, dirty moleskin trousers, and old soft felt hat. Can be identified.

Design and Methodology

The pale colour palette design has revealed the data in a new way, allowing the user to gain insights into crimes that may not necessarily have been easily found in the gazettes.

For Brett’s methodology he took the simple approach, using the Trove API, to count how many times a word or phrase (known as an n-gram) appeared in a given year, and to see how that changed over time.

‘I didn’t look for context, so with few exceptions, the code makes no distinction between whether, for example, it was a Panama hat that was stolen, or the Panama hat was worn by the (alleged) suspect. The same approach was taken with places: it didn’t matter whether the crime took place in Dubbo, or the person was originally from Dubbo, or the person was ultimately sentenced in Dubbo, merely that the ‘‘Dubbo‘’ appeared in the gazette in a given year.

These tallies are then normalised against the total number of words in the gazette for that year, so that words or phrases that appear in years where more crimes and events were recorded (and hence there are more words) aren‘t given undue weight. The results are then graphed to show the changes over the years.’

You can read more about Brett’s methodology here.

Dealing with Historical Data

A significant issue that arises when working with historical data is what it reveals about the time it was collected. As a technologist extracts data from historical records, to show in a contemporary and new experience, it can bring up issues that may be offensive and confronting in today’s context. As there is little curation over this particular data set, but rather a decision based on the design and how the data is viewed, the way this information is experienced can be very problematic. We need to reveal the information, in this case relating to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, that was collected by police from c 1860 –1930. We are mindful and concerned however about how this gets interpreted today.

The Library’s Indigenous Engagement Manager, Damien Webb reveals:

‘Perhaps the biggest issue when working with colonial-era collections (and in particular those of the police and government) is how easy it can be to accidentally recreate or reinforce racist ideas and biases. The idea that uncurated data is neutral data remains deeply problematic and we now know that some sources require additional contexts to be considered culturally safe. To bring awareness to these biases in a way which clearly illustrates the limitations of colonial records in regards to Aboriginal identity and agency is an ongoing challenge.’

We hope you find this data visualisation of the New South Wales Police Gazette & Weekly Record of Crime interesting. Read more about this project in this article on The Conversation. The complete code for this experiment has been open sourced on Github.